Why Some AI Labs Build Better Models Than Others

- Nikita Silaech

- 2 days ago

- 3 min read

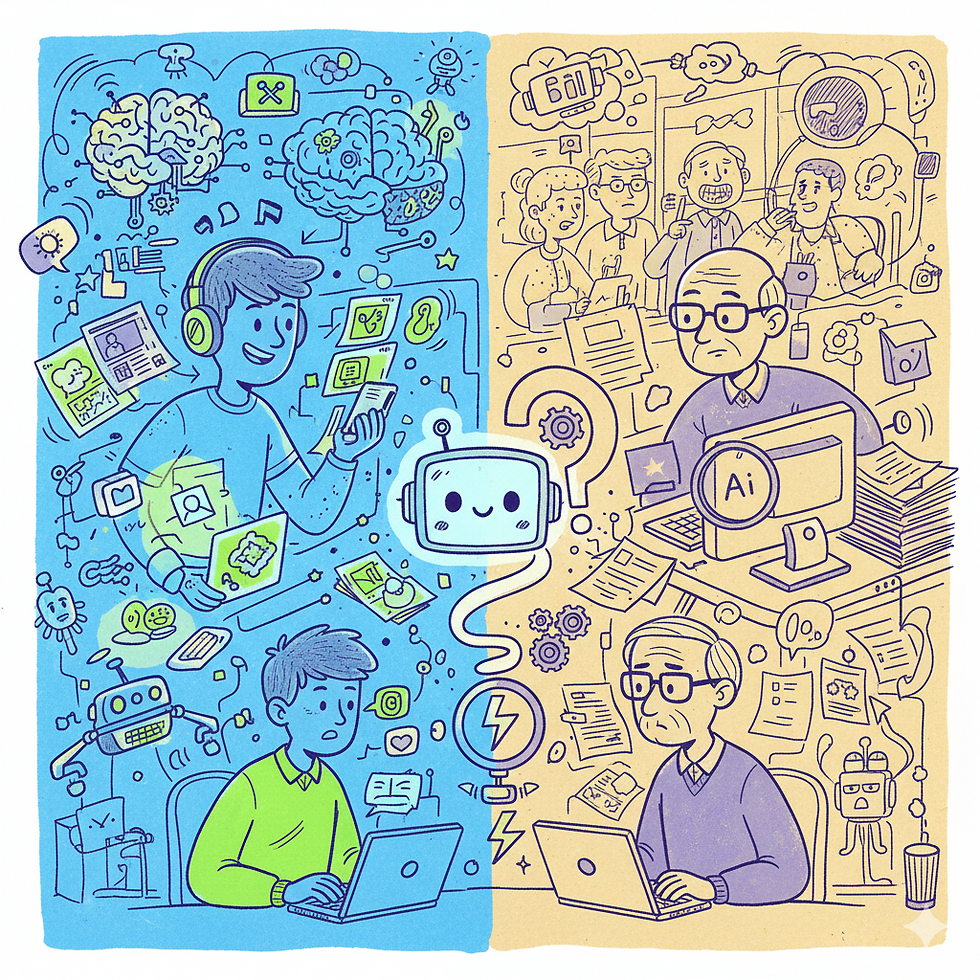

The gap between foundation models produced by different AI laboratories is not primarily a computing gap. Two organizations with access to similar hardware and data often produce wildly different capabilities. The divergence suggests that something beyond resources drives model quality. Some of these factors include organizational structure, research culture, hiring philosophy, and how teams distribute expertise matter profoundly.

Take Antropic, for example. Founded in 2021 by former OpenAI employees, the company now attracts talent at rates that prove how organizational factors have competitive weight. Engineers at OpenAI were eight times more likely to move to Anthropic, while the ratio from DeepMind was 11:1 (Fortune, 2025). It’s surprising that a smaller, newer company is consistently winning the bidding war against both OpenAI and DeepMind despite those organizations' larger resources and brand recognition.

On top of that, Anthropic maintains an 80% retention rate for employees hired over the past two years, compared to DeepMind's 78% and OpenAI's 67% (Fortune, 2025).

When talented researchers leave and experienced ones stay, organizational knowledge structures differently. The teams that retain people build cumulative institutional understanding of why specific architectural choices worked or failed, what data properties matter for different problems, and how to debug large-scale model training issues. Knowledge of this depth cannot be reconstructed quickly when people depart. It lives in conversations, in pattern recognition that experts have internalized, in why certain experiments were run and others rejected.

The research culture distinction appears in how different labs approach model development. One observer noted that "if Google is run by engineers and Anthropic is run by philosophers, OpenAI seems to be run by product managers" (Understanding AI, 2025). The statement is a description of different optimization pressures. Product managers optimize for velocity and market impact. Engineers optimize for technical elegance and correctness. Philosophers optimize for reasoning about tradeoffs and first principles. Each produces different model architectures, different safety investment levels, and different decisions about what capability to prioritize. None is universally superior, but each reflects the values embedded in the organization's decision-making structure.

Hiring practices amplify these differences. Anthropic explicitly attracts researchers by offering "intellectual discourse and researcher autonomy," positioning itself against Big Tech's inflated salaries and brand cachet (Fortune, 2025). OpenAI has historically hired for product shipping speed. DeepMind has invested in hiring elite academic researchers from specific universities and research communities. These choices don’t just shape who arrives, but what problems get framed as important, how failure is interpreted, and what constitutes publishable research.

The organizational structure itself, often creates constraints. Some labs use centralized research groups where a small number of senior researchers guide most decisions. Others distribute decision-making across pods or teams. Some labs maintain strict separation between research and deployment. Others integrate them tightly. These choices determine how fast innovation propagates, how much exploratory research gets done, and whether junior researchers can pursue unconventional directions without approval from seniors.

There’s also the fact that expertise cannot be scaled linearly with hiring. Bring in fifty brilliant researchers and you don't automatically get a team that's five times as good. You get coordination problems, communication overhead, and reduced autonomy for individual researchers. The teams that perform best typically have fewer but more knowledgeable people working tightly together with clear decision-making authority.

This suggests why Anthropic, despite being smaller, produces competitive models. The organization accepts lower total research throughput in exchange for tighter feedback loops, more researcher autonomy, and lower coordination overhead. DeepMind and OpenAI have scaled to the point where they need elaborate management structures just to coordinate across all their research groups. That creates capability in breadth but can fragment excellence in depth.

Compute and data are necessary but not sufficient conditions for model quality. How you organize people, how much autonomy researchers have, how you hire, how knowledge accumulates and propagates through the organization, are competitive advantages that don't show up in any single metric but compound dramatically over time. Organizations that fragment researcher authority or incentivize shipping over depth will eventually face a skill cliff. The work gets harder, the problem-solving approaches more brittle, and the junior researchers never develop the intuition that senior people built through hands-on debugging over years.

Comments